Wang Wei the Precursor

Late in life, I enjoy only quietude

far from my mind the futility of all things;

Without resources, remains the joy

to wander in my old woods

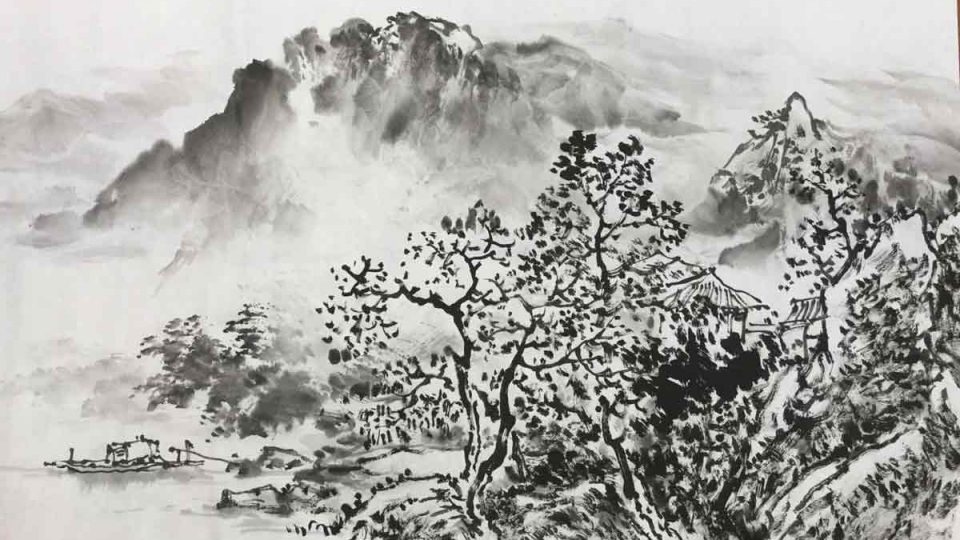

Pine breeze unties my belt

The moon strokes gently the strings of my sitar.

What is, you are wondering, ultimate truth?

Fisherman’ song, in the reeds, that fades away…

Wang Wei (699-759)

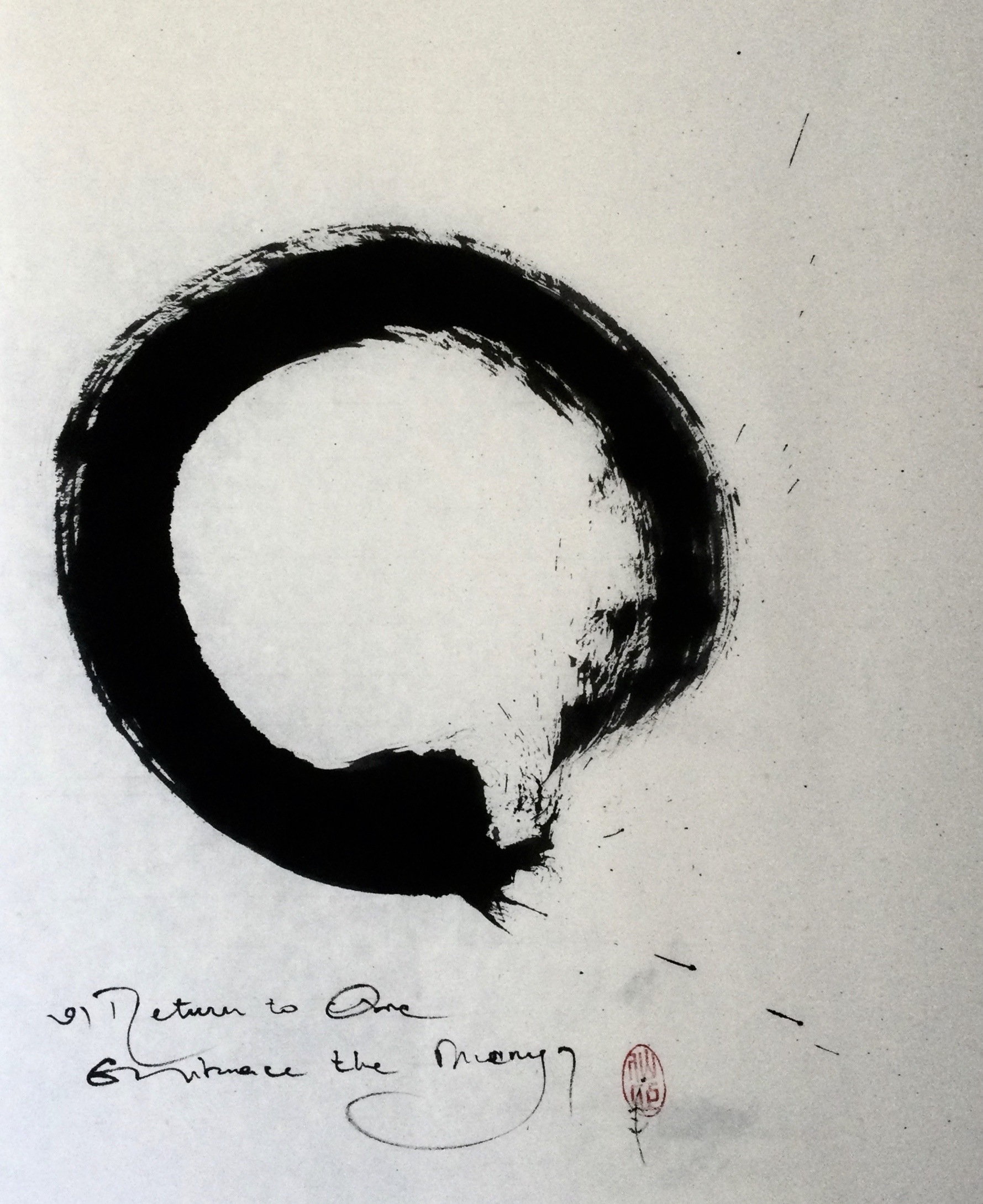

Chan does not give much credit to the orthodox Buddhist religious approach with its rituals, texts, images and symbols, those being considered obstacles to spiritual realization which can only be the result of personal experience, direct and immediate, and can only be transmitted from mind to mind.

According to Ryckmans “through its extraordinary insistence on objective reality, Chan has encouraged a humble and mindful contemplation of the world, in its most trivial, minute, concrete manifestations.’’

Following the Heart Sutra, – emptiness is no other than form –[1], the Buddha’s truth is in the truth of reality — ordinary, unique and specific:

– Who is the Buddha?, the disciple asks.

– It’s a three pound turnip, answers the Master.

Therefore monks and Chan followers looked for means other than words and religious representations to express the ineffable depth of their spiritual realization. As the saying goes, ‘how to explain the taste of brown sugar to someone who has never tasted it?‘

During the Tang dynasty (618-907 C.E.), Buddhism became strongly implanted in Northern China. It inspired a refined, vivid and colorful religious art, similar to Persian miniatures as can be seen in the famous Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road. In addition, artists excelled at descriptive painting decorating palaces and tombs, as well as personages and horses.

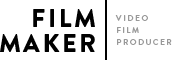

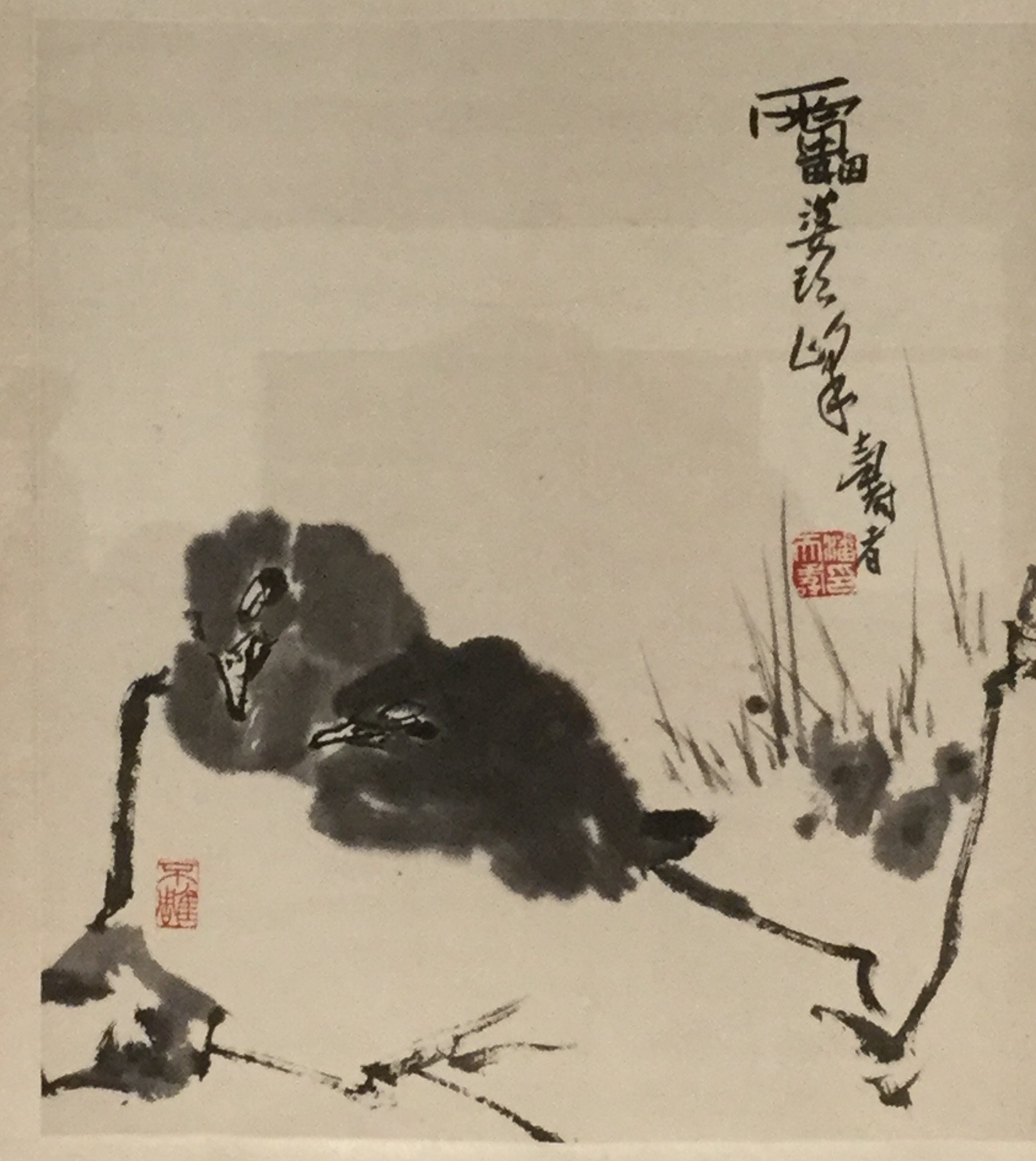

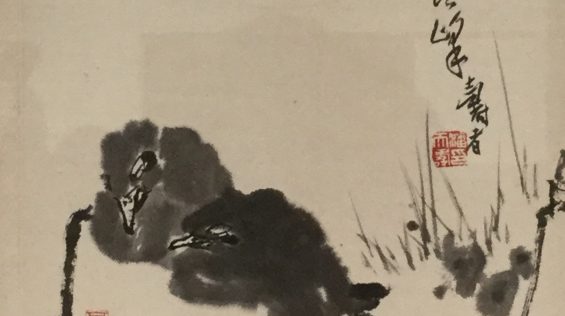

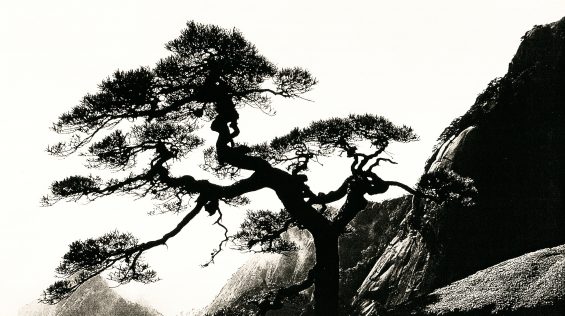

But it is in monochrome landscape painting (shanshui, mountain and water) that an historic aesthetic revolution occurred, a radical change of paradigm. Naturalist landscapes gave way to landscape painting on silk or paper using wash drawing technique, where empty space played an important role. The origin of this revolution is generally attributed to the painter-poet Wang Wei (699-759). Despite the fact that none of his paintings have survived, it’s said that anyone who saw them exclaimed, ‘’It’s impossible to go further, higher, the art of landscape painting has achieved its final act!’’[2] That was thirteen centuries ago…

Wang Wei successfully passed the Imperial exams at a very young age. His life was spent between the honors of official positions and long periods of exile. He finally retired from the world to concentrate on his work and spend the rest of his life as a hermit-monk.

Painter, poet and a Chan practitioner, Wang Wei is a precursor of the ideal of great scholar-painters, calligraphers of high education and culture, whose careers fluctuated between political and administrative affiliations. The rise of this new elite – the literati – was made possible by the Tang Code, which opened the door to passing the Imperial exams to all, not only the previously favored aristocracy. These literati, many of them voluntarily refusing official positions, as fringe amateurs, or dilettantes, enjoyed calligraphy, poetry and painting, the three aesthetic skills considered to be the same artistic discipline.

Of Wang Wei it is often said, ‘’When you enjoy a poem by Wang Wei, it suggests a painting; when you contemplate Wang Wei’s paintings, there is poem in each of them.’’[3] Like poetry, Chinese monochrome landscape painting is not descriptive but allusive; it does not illustrate feelings, it only suggests with a few brushstrokes a spiritual experience of the world, and that is why poetry and Chan painting are perfectly exchangeable. Or in Shi Tao’s wording:‘’Painting is the very essence of poetry and isn’t poetry the Chan (spiritual truth) of painting?’’

In poetry, like in painting, Wang Wei expresses in a very Chan way the paradoxical reality between existence and non-existence, since the ultimate truth is not somewhere else: it is here, right in front of us, fleeting, as evanescent as a fisherman’s song or in weight of three pounds of turnip.

And, you wonder, what is ultimate truth?

Fisherman’s song, in the reeds, that fades away…

Wang Wei’s painting is explained thus by Carré: ’’painting centered on emptiness and on the play of absence/presence where unseen ultimate reality (evanescent summits lost in white clouds) is even more present…’’

Despite the fact that we cannot contemplate any of his original paintings today, only bad copies, Wang Wei left an important collection of poetry – where one can see his paintings… – and a short text that expresses the essence of landscape painting and his unorthodox style which, during his time, was an aesthetic and spiritual revolution inspired by Chan. After some technical advice, Wang Wei gives us the essence of his creative approach:

‘’Keep the ink stone in your hand and, from time to time, just space out in a ludic contemplation. After many months or even years, you will slowly reach a subtle and mysterious state… Enlightenment does not need extensive discourses.’’

Even though Wang Wei was never recognized by Chinese critics, like Su Dongpo for instance, as the greatest painter of his time, they all perceive in his work an ineffable truth beyond mere appearances, beyond what could be seen by the eyes, beyond what could be heard by the ears. That is Wang Wei‘s spiritual heritage to future generations of artists. As for regretting that none of his original paintings have survived until today, this is probably Wang Wei’s last teaching, in a perfect Chan spirit:

“Since the purpose of this painting tradition is to fade in the mist of all-presence, it finds

paradoxically in this very absence its perfect achievement!’’[4]

_____________________________________

[1] In the Heart Sutra’s formulation that we have seen earlier.

[2] Carré P. in his translation of Wang Wei ‘s poems :’’Blue Seasons’’

[3] – Quoted by N. Vandier-Nicolas

[4] – Carré P.

Comments (0)

Leave a reply