A ludic contemplation

Your heart should be absolutely empty,

Without the slightest hint of dust,

And landscape will emerge from the depth of your soul.

Wang Yu (17thc.)

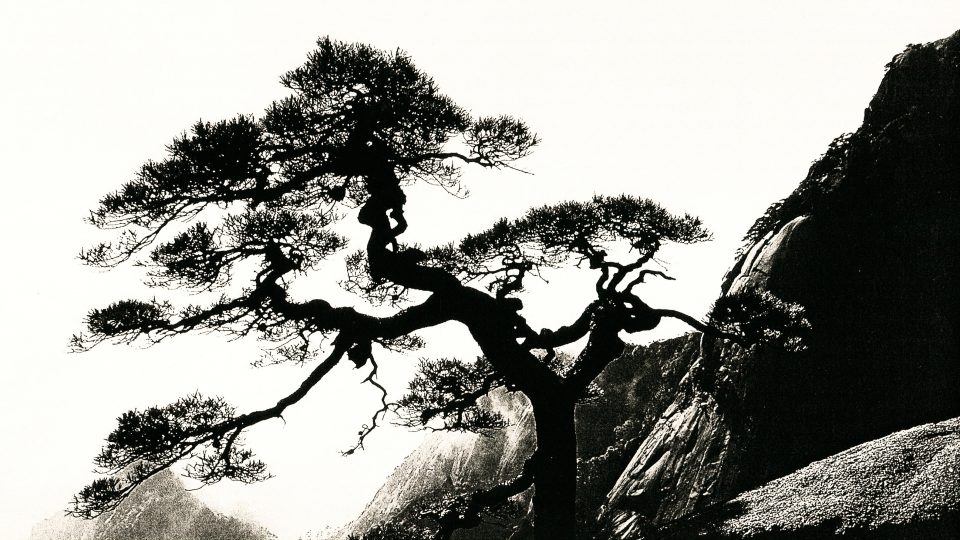

In the Chinese tradition, to be recognized as a spiritual (Chan) artwork a painting should be both vast and tortuous. This describes the painter’s state of mind as well as defines two main techniques of Buddhist meditation :

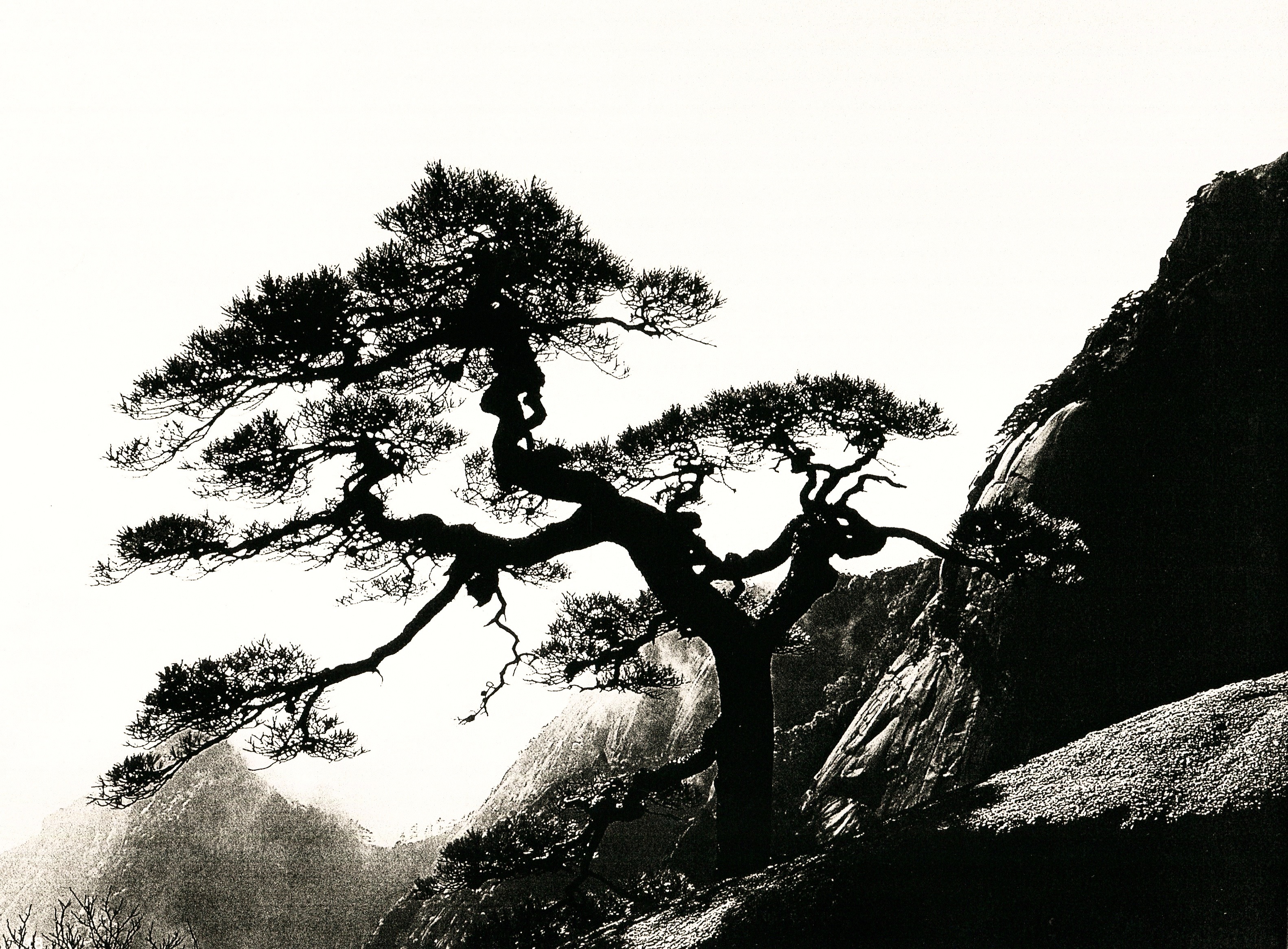

– A peaceful mind comes from the vast and silent background. This opening towards limitless space will appease the mental agitation of “anxious souls worried by secular life” in He Qing’s well-known expression. The peaceful mind will become like the smooth surface of a great lake. These spiritual practices are called mindfulness and concentration ( shamata). Most use one’s own breath as the main support for concentrating one’s full attention.

– A deep or ‘tortuous’ introspection, as the Chinese call it, because the path is not obvious and the skill can only be achieved by a deeply penetrating insight (vipassana) to recognize the mind’s true nature and thereby be free of the unlimited tricks of ignorance. Once the mind is calm and concentrated, its true nature can shine forth in all of its depth, like observing the bottom of a lake after the waves have ceased.

Like the term “Zen”, the word “meditation” is overworked in our modern culture. Nowadays everyone is meditating in front of a beautiful sunset or even while walking their dog. However, in Buddhist terms, meditation means to practice or to train at something, like practicing yoga or a martial art, or for that matter, practicing Chan painting. It consists of spiritual exercises and techniques, not only of relaxing moments when the mind wanders about its own little business..

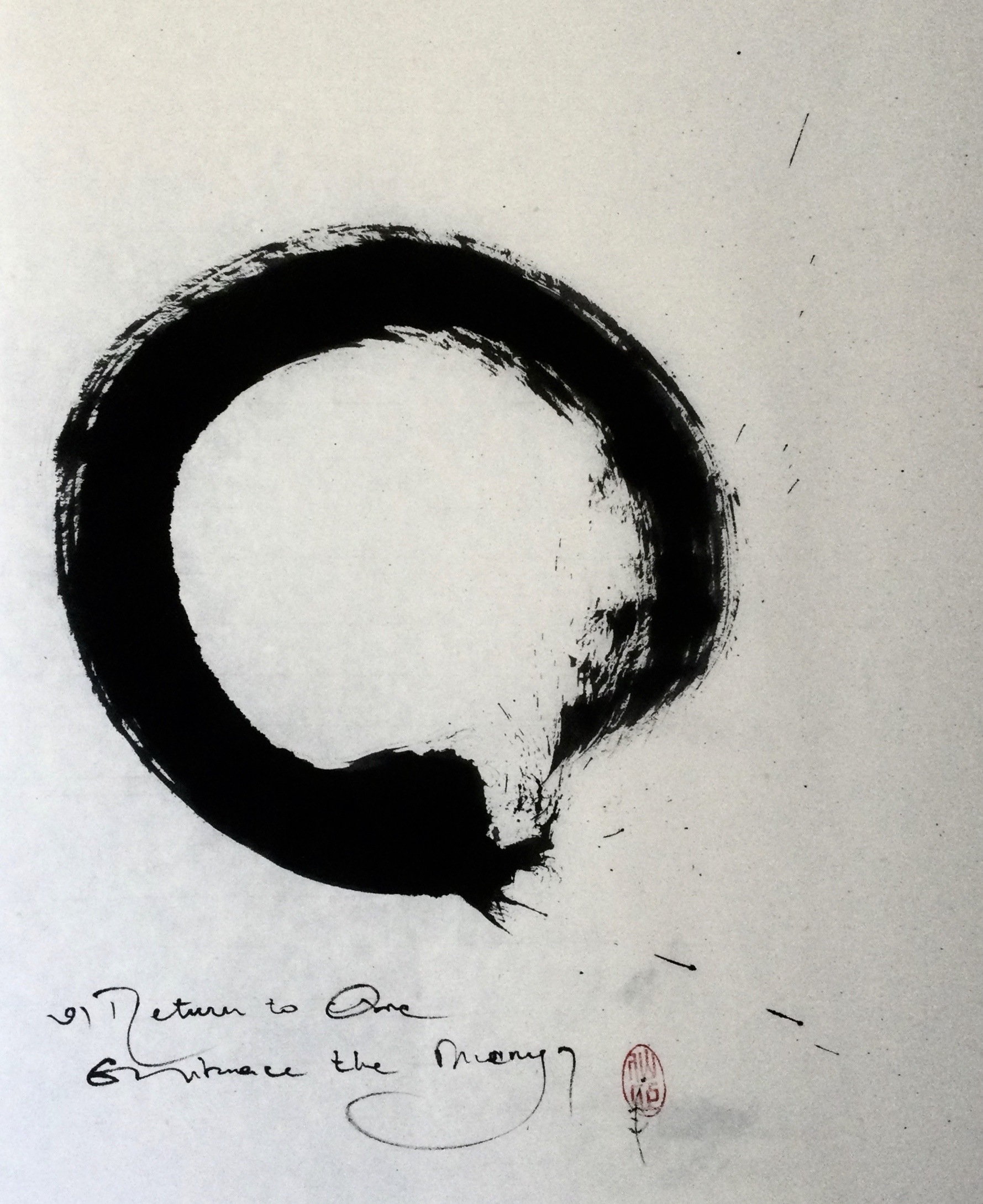

In monochrome landscape painting, whether Chan or Sumi-e, empty space plays a key role as a suggestion of Buddhist emptiness or Taoist void. Therefore it seems all too natural for a Chan spiritual painter to express the inner (non-existent) nature of things to first recognise this empty nature within himself. Therefore a meditation practice, even minimal, seems to me a preliminary step toward the path of spiritual painting following Wang Yu’s recommendation quoted above. In other words, in meditation as in spiritual painting, one should step in the background to cut any wanting to achieve or any conception of an aim to reach ; here the path and the aim are one.[1]

To ‘empty one’s heart’ and remove the dust, one should start by pacifying mental agitation and intellectual fabrications and, above all, by cutting through ego-clinging — otherwise ‘me-myself’ could end up thinking that I am painting which might become quite pathetic! Loosening one’s narcissist, egoistic stranglehold can open the door to more insightful creative intuition which will be then transmitted directly to the brush.

By connecting with our empty inner space, we will connect naturally with our heart-mind: “When you silence your mind, it will confide in your hand.” or in Michelle Billaud’s words, “For me there is no hierarchy between my spiritual practice and my painting. Spirituality is a state of being in full awareness which will echo in all activities, including painting of course. When I paint, I feel free. This is not a mental state nor concept, it’s a state of harmony, like during meditation.”

As Shi Tao described it, a first stroke on white paper cannot be taken lightly. A single brushstroke brings life into vast empty space and give direction to the primordial chaos; it is the first link between man and sky : “a single brushstroke is also the ‘Unique Brushstroke’ (…), the origin of all things, the root of all phenomenon.”(1) This aesthetic and spiritual commitment requires a moment of preliminary contemplation since one cannot do anything well without putting first oneself in the proper disposition to do it, without cutting through pre-existing mental agitation and concepts. For monks, thus was the role of the cloister, a transitional path to shed all unnecessary sentiments and enter into the necessary concentration for the ritual to come. For us, acrobats of the brushstroke, ascetics of the ink, our cloister starts by a ritual concentration in the proper and precise arrangements of our workplace, and in the initial, quiet stirring preparation of the ink in the stone.

As explained by Wang Wei in his Painting Secrets, “Keep the ink stone in your hand and from time to time, let yourself merge in a ludic contemplation. After long months or even years, you will enter a subtle and mysterious dimension.” Wang Wei’s words are more ”subitist”(2) than they seem at first: for in this calm and ordinary contemplation, the act of painting itself becomes a form of enlightenment.

Meditation

Start by generating a vast limitless mind.

Goenka

But if Wang Wei’s mind and ours are identical in essence, it’s a gross understatement to affirm that his world and ours are quite different. It seems therefore that Wang Wei’s advice is not sufficient to pacify today’s agitated minds. For contemporary artists looking for a spiritual art, they should support their creativ

e work by a solid meditation practice; since, as we have seen, the Chan attitude of the painter gives a spiritual dimension to a painting — not the other way around.

Among the variety of meditation techniques, including analytical meditations, I would like to propose a technique combining dhyâna and prajnâ – meditation and wisdom — in line with Chan tradition and aimed at a spiritual painting practice.

> It is usually recommended for beginners to multiply short sessions of meditation (5 to 10 min.) rather than longer sessions which are often spent between mental agitation and drowsiness. Some schools advise to close your eyes, others to keep them half-closed in the natural prolongation of the nose, others still to stare with your eyes wide open into empty space. In my opinion, in the beginning, keeping your eyes closed helps to establish a deeper concentration, but everyone should find their own comfort.

> On the other hand, all schools insist on the importance of a good posture to avoid drowsiness, tensions or mental agitation and to help the circulation of energy in the body. The main recommendation being to keep the vertebral column straight whether sitting on a chair or on a cushion since as Chan masters put it, “if the posture is straight, the mind will be straight too.”

The same criteria apply to painters in order to obtain the same result, with the only difference being that energy should circulate in the body to finally reach the tip of the brush.

Pacifying the mind

As the adage goes, if you want to pacify your sheep, give him a vast and spacious meadow. Thus Goenka’s advice is to ‘start by generating a vast limitless mind’. During these moments of silent contemplation, time slows down, space expends and a torrent of wandering thoughts naturally begins to decrease since they are no longer fueled by an unsteady mind.

The best technique to pacify the mind and negative emotions consists in letting consciousness rest single pointedly on an object of concentration. Different schools emphasis different techniques but in Chan painting approach, I recon, the most appropriate is the observation of the breath. Using breathing as a concentration support is a way to understand one of Xie He’s painting principles, the vitality of the breath (energy, Qi) which will be with us all along our painting practice. In Tibetan texts, it is often mentioned that “mind rides the breath’’ since by pacifying one’s breath, mental agitation begins to settle down quite naturally.

Meditation Session:

Having found a comfortable position with a straight spine, bring your attention on the contact of the air coming in and going out at the tip of the nostrils. Without following the flow inside and outside, without judgement, just observe the sensations generated by the passing air at the tip of the nostrils. Like a revolving door, air comes in, air goes out. Remain fully aware of the tenuous contact, like a woodcutter’s attention on the unique contact point between the saw and the log. Observe; they are sensations arising at the tip of the nostrils, pleasant or unpleasant, tickling, scratching, dry or humid, cold or warm, which appear and disappear in the inner part of the nostrils or at the base of the nose. When your mental agitation calms down, it is possible to decrease the size of the concentration point, until it becomes no bigger than the point of a needle and remains, naturally.

If you encounter difficulties entering a state of deep concentration, it might be helpful to count your breaths from 1 to 10 and from 10 to 1 in your most concentrated total mindfulness, without forgetting any number, before going back to the contact of the breath at the tip of the nostrils.

As soon as you realize that your mind has escaped into past or future wandering thoughts, bring it back gently at the tip of the nostrils, like a butterfly landing on a flower after having twirled around aimlessly, and return without tension to your concentration point.

Slowly, while remaining fully aware of your breath in and out, you can bring your attention on the suspended instant between the end of the expiration of one breath and the next inspiration: a lucid and clear instant, free of thoughts, vast and limitless like space, which is nothing else than the natural state of the mind.

Unifying space and consciousness

Sooner or later, a sensation, a muscular tension, a pain or a noise will arise. Observe it as it is, without judgement and recognize its nature. “There is a tickling sensation” or “There is a noise.” By simply observing it, it will vanish as naturally as it had appeared, like a wave on the ocean.

Apply the same observation to an arising thought: it is impossible to prevent it to arise since it’s already here. Observe it as a simple thought not like as an object, observe its transitory translucent nature and don’t feed it with associations or judgements. It appeared, it remains and then disappears. Observe where it came from, where it remains, and where it disappears. This technique of observing the thoughts comes from Bodhidharma himself:

“When a thought arises in your mind, be aware of it.

As soon as you are aware of it, it will disappear.”

When the thought subsides like a wave returning to the ocean, let your mind remain peaceful and calm in a clear consciousness without conceptualisation. Slowly we can enlarge this consciousness, pushing back limits further and further until it becomes as vast as space – vast, vast, very vast, vaster, even vaster[3] – until it covers limitless empty space. Remain fully absorbed in this immutable non-dual nature of the mind, limitless like empty space, emptiness and clarity inseparable.

In Kalu Rinpoche’s spiritual advice:

Wherever there is space, there is mind.

Wherever there is mind, there is consciousness.

Let your mind rest in the empty-clarity of consciousness, without distraction.

Then maintain this inner state whatever you do.

Chan texts often encouraged dhyâna practitioners to meditate in nature, the contemplation of vast horizons being a recommended exercise. It seems obvious that Chan painters would not wander on mountains and solitude just to observe bamboos curving in the wind or to “feel nature” as recommended by Li Xiang Hong. The purpose of contemplating far horizons is to merge consciousness and empty space, and to keep the mind in this great open state without conceptualisation nor a single reference point. This spiritual practice is one of the highest Chan teaching on the nature of the mind – also practiced until today in contemporary Mahamudra and Dzokchen Tibetan schools.

Finally, emerging from this non-dual meditative absorption, mind-heart free from the worldly dust, one can then take the brush “and the landscape will emerge from the depth of the soul”. In this post-meditation phase, the meditator is advised to remain in perfect equanimity towards whatever appears, to be like “the child of illusion”. As a dreamer aware that he is dreaming, as the yogi free from the play of appearances, as the Chan painter who knows that at the end there is again a mountain,

“As a fish playing with the waves…”

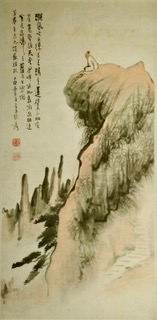

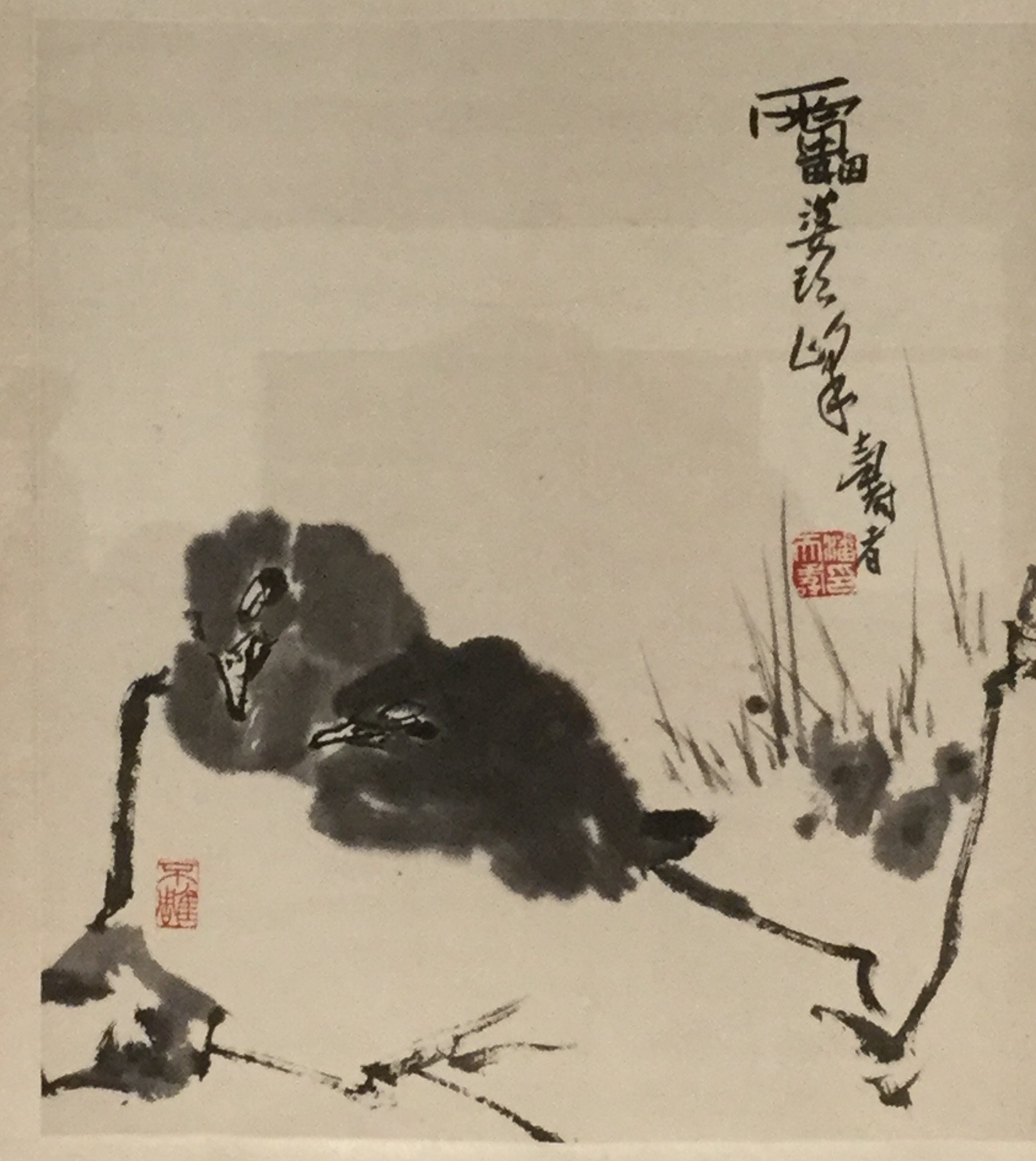

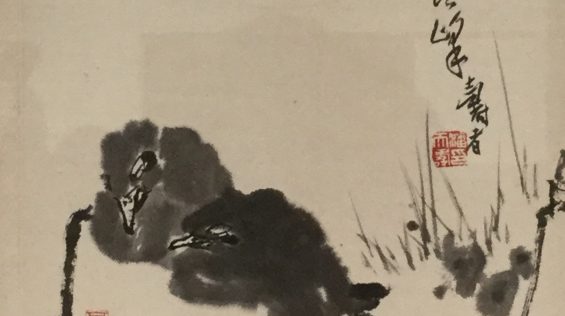

Would that really be a coincidence if, at the end, there were again Chu Ta’s Fishes among rocks?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

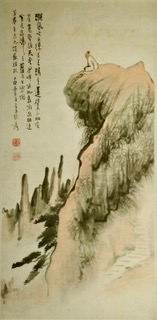

Chu Ta (1626-1705): Player in the Waves

[1] – Cf. the 3 grounds: foreground, background and middle ground in Chapter

[2] – ShiTao (1638-1720): ‘’Comments on painting’’

[3] – Which is the translation of the Prajanaparamita mantra: ‘Om Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi, Soha’.

Comments (0)

Leave a reply