Li Xiang Hong : private demo 2016

A new paradigm

‘’A pictorial representation should arouse in the spectator thoughts or feelings close to those which would arise from the real object or the scenery itself.’’

In the West, it was only in the second half of the XIXth c., after Monet’s 1872 painting, Rising Sun, that this aesthetic theory was seriously questioned; while in China this idea was challenged as early as in the XIth c. by Song Dynasty literati painter-poets.

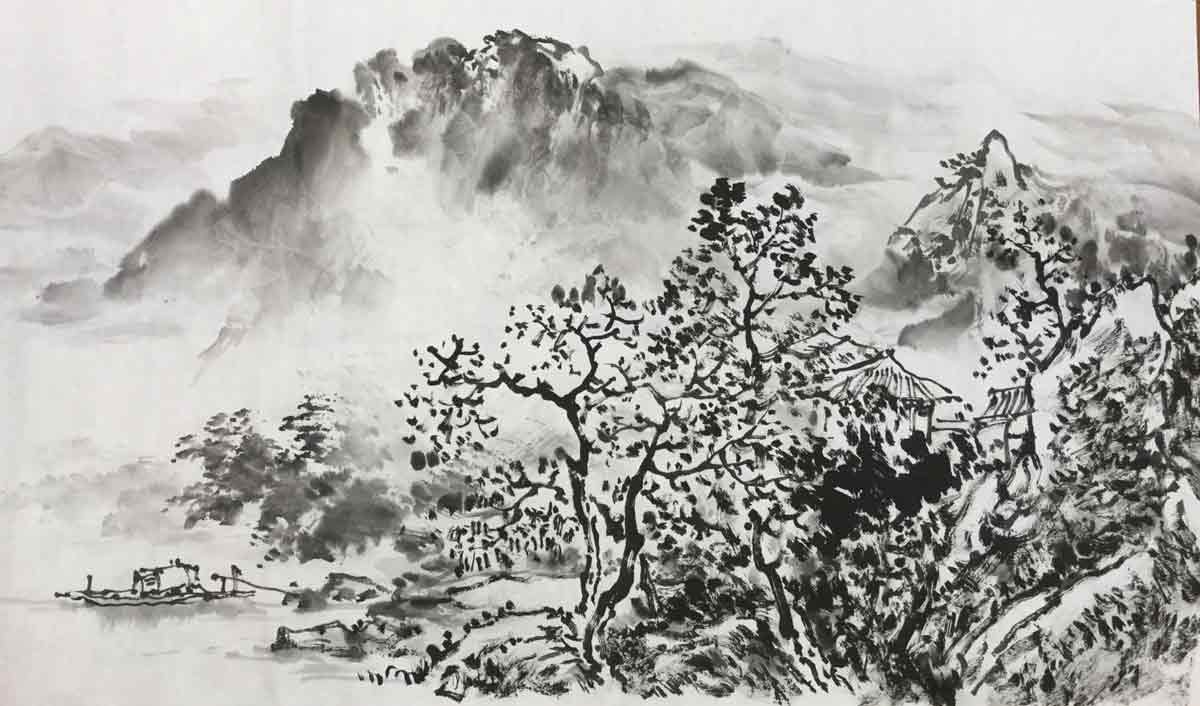

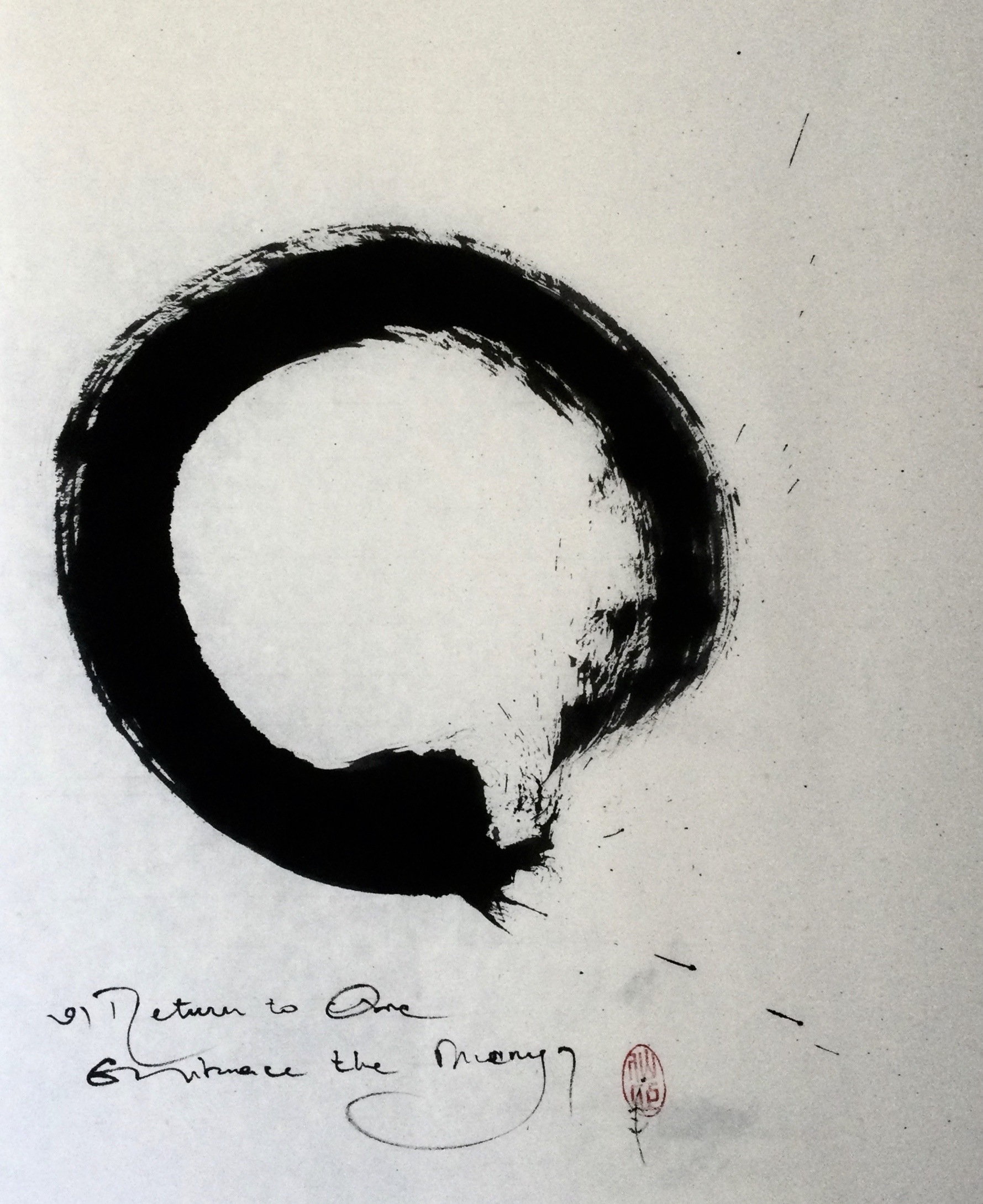

Following the precursors like Wang Wei, at the turn of the millennium, conformity of a painting to outer form, i.e. mere resemblance, could no longer describe the expressive quality of non-orthodox styles that were flourishing in China for a few centuries and which could be called conformity to the spirit (of the painter and/or of the subject). For Su Dongpo (alias Su Shi, 1036-1101) ‘‘as a painter, looking for resemblance only is childish’’, meaning that real painting is elsewhere. For the first time, he established a parallel between the Chan path to Enlightenment and the path of spiritual painting. “Between Chan and poetry/painting, no difference: the awakening (wu) of the brush is like Chan enlightenment.’’ The scholar-painter is thus identified by analogy to the wise man in his quest for wisdom.

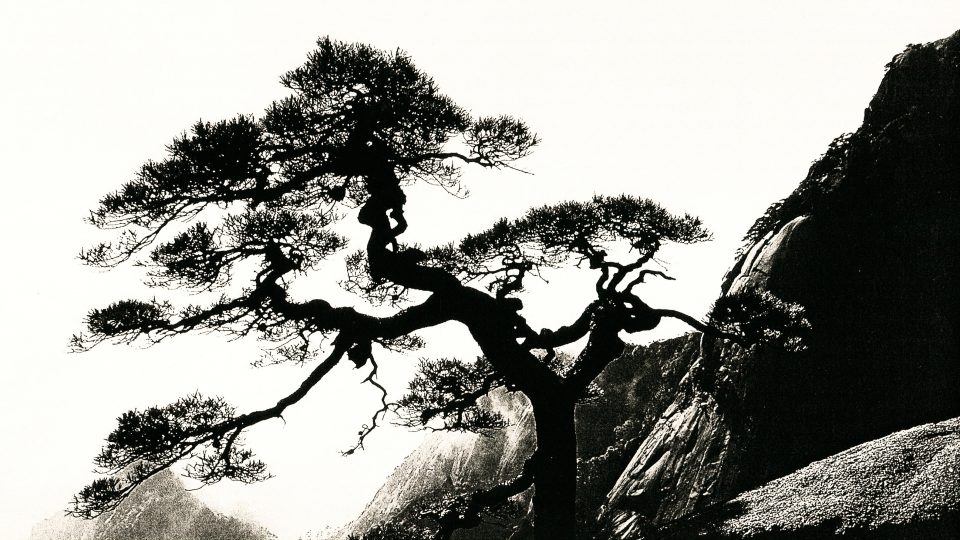

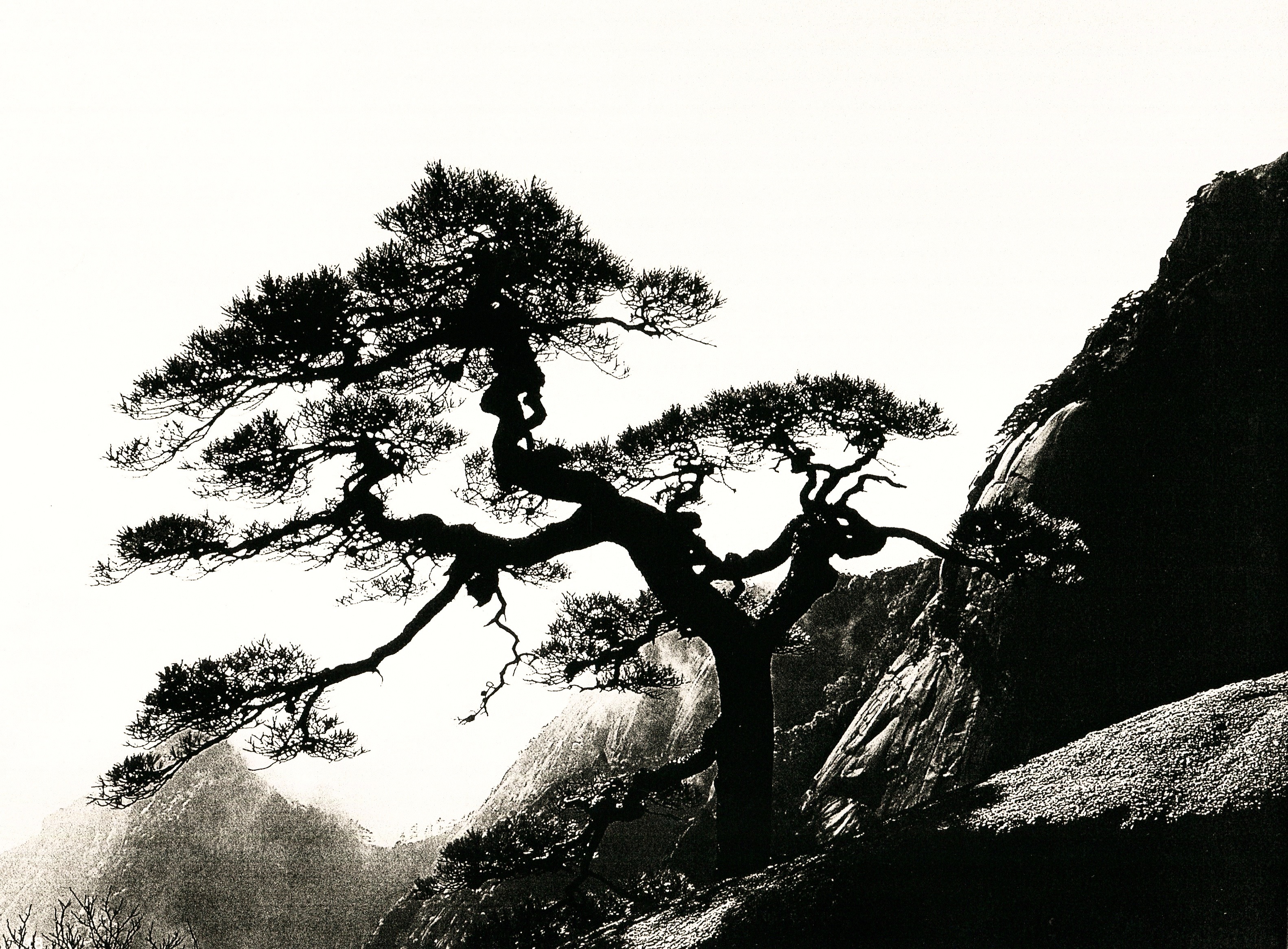

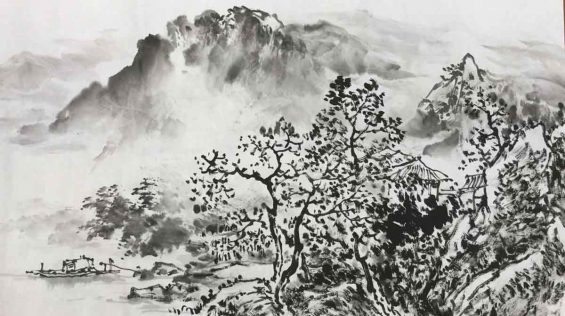

Despite the fact than Chan shanshui painting never really existed as a separate school nor a chan painting style was never recognized as such, for most Chinese commentators links between Chan subitist approach and spiritual monochromatic landscape painting cannot be denied. For the purpose of Chinese painting in general and shanshui landscapes, in particular, is to free painters and spectators from the “dust of the world’’ and to immerse them into a deep inner spiritual silence. Like He Qing, for example, for whom ‘’the spiritual limpidity of landscape paintings is the very soul of Chinese painting’’ or N. Vandier-Nicolas for whom “the influence of mystical thinking on Chinese art is a given fact throughout and that of Chan on landscape painting a total evidence.’’

Therefore this new paradigm can be define thus: Among the literati scholars-painters of the Song dynasty, a trend of painting in search of wisdom left behind the established banks of mainstream naturalism and conformity to the form only, to dissolve in Chan emptiness and to reappear from the mist, spiritual, intuitive, suggestive and free from constraints (yi pin). And these two approaches should not be confused, either, in the same way that the mountain of the beginning and the mountain of the end should not be mistaken.

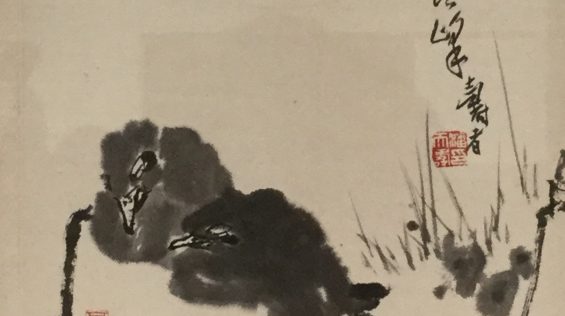

In other words, some painters inspired by the Chan mind – monks or home Buddhists, hermits or scholars, divine madmen or civil servants on the run – refused to become instruments of official propaganda and to abide by court style often defined by the emperor himself. They reinterpreted the techniques and spirit of Song intellectual literati painting to express their own spiritual realization. Thus, outside the standardized court academism, there appeared an unorthodox painting style which found in nature an inexhaustible source of images and symbols, and a pictorial language to express its spiritual experiences.

According to He Qing, Chinese don’t look at nature for its own sake as the love of nature is not merely pure romanticism. ‘Chinese painting is an open space where the painter’s inner silence and nature’s silence melt and rise in a cosmic and metaphysical silence’. This is a pure selflessness as expressed by the old Taoists or in the concept of emptiness in Chan Buddhism. Renouncing honors and official sinecures, these poet-painters found in the mountains a perfect refuge since, in the words of F. Cheng, ’’mountains are for Chinese people the place par excellence of renunciation to the world, as well as of a spiritual path.’’

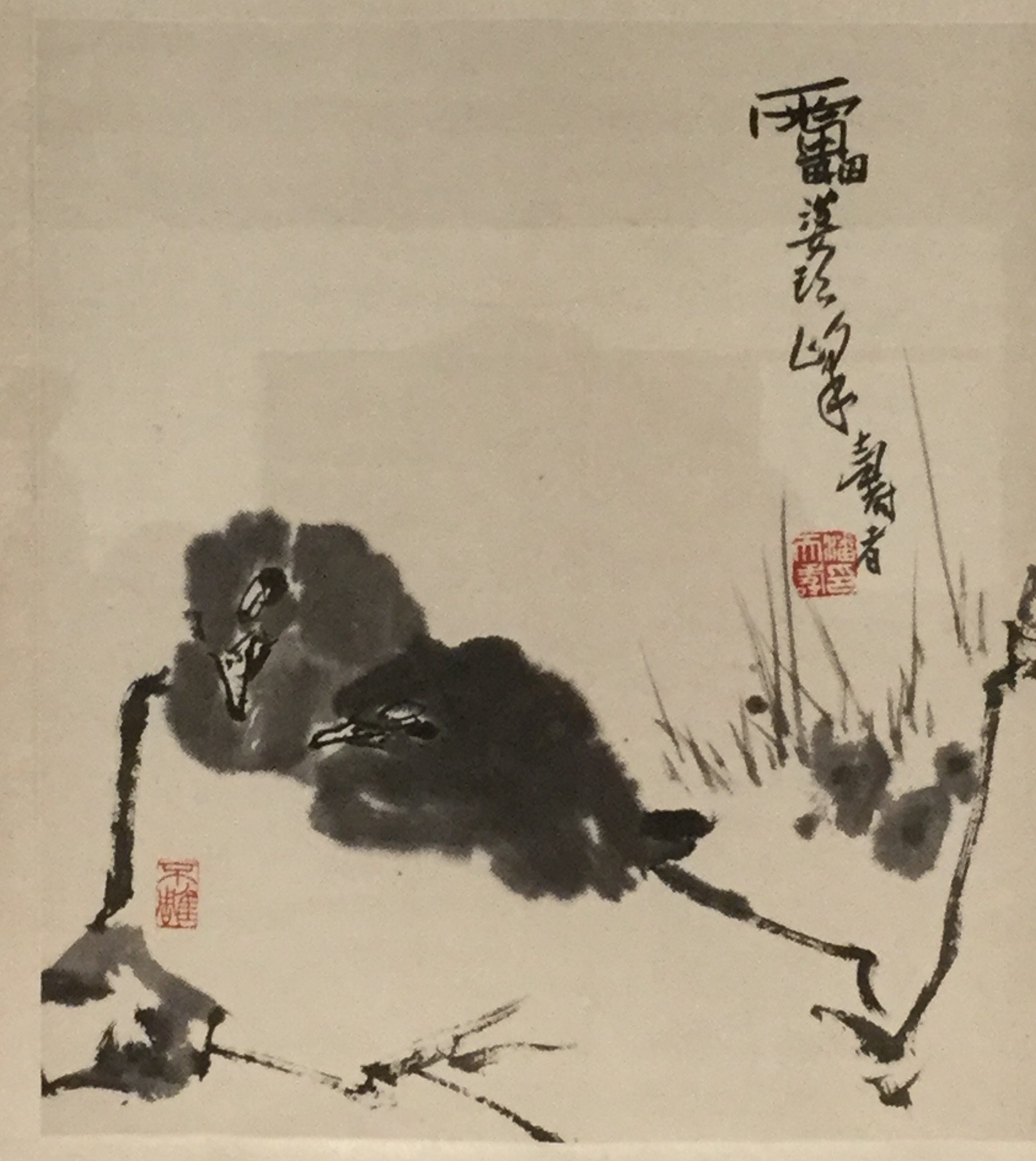

Without ever becoming a school, Chan painting with its spiritual qualities like empty space and contemplation, a taste for silence, simplicity and solitude, as well as a deep love for nature, was exported to Japan from the XIII th c. This began with Wang Wei, first and foremost, as a precursor, followed by the Chengdu exiles who invented the style “without constraints’’ (y’i pin), among Song literati leaders, like Mi Fu (1051-1107) and the famous Mu Qi, still considered in Japan as the greatest painter of all time[1]. We find its trace among hermit monks or in the Individualists or the Eccentrics, from Xiu Wei to Chu Ta and closer to us with Pan Tianshou, who ended up a victim of the monolithic, normative thinking of the Cultural Revolution.

[1] – On Mi Fu life and work, see Nicole Vandier-Nicolas.

[9] – Concept emprunté à Lacroix A. : ‘Déliés, plutôt que pleins’ dans la revue Philosophie, été 2017. Nous pourrions dire : à la fin il y a de nouveau la simplicité.

[10] – Trente rayons convergent au moyeu mais c’est le vide médian qui fait marcher le char

[11] – Cheng F. : Le livre du vide médian, p.9, Albin Michel 2004

[12] – A lire les belles pages de N. Vandier-Nicolas dans : Art et Sagesse en Chine, op.cit. p.68 et suivantes.

[13] – Su Tongpo (XI°s.) cité par Cheng : Souffle-esprit, p. 85, Le Seuil, Points essais

[14] -Yolaine Escande propose une autre interprétation de ce vide : il est volontairement laissé par l’artiste pour qu’éventuellement l’Empereur puisse y apposer calligraphie et/ou sceau ! Ces deux interprétations pouvant d’ailleurs cohabiter.

Comments (0)

Leave a reply